Jakarta, 9 April 2021. The government through the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) recently announced a Long-Term Strategy to achieve carbon neutrality and climate resilience. The strategy stated that Indonesia will become carbon neutral in 2070. As indicated on the strategy document, Indonesia’s emissions are targeted to reach a peak in 2030. In the formulation of a target, it is necessary to have clarity regarding policy support for each sector to reach peak emissions in 2030.

As a party to the Paris Agreement, the 2070 carbon neutral target is inappropriate and less ambitious.

Collaborating with the Yayasan Madani Berkelanjutan, ICLEI Indonesia, Walhi, and supported by the Thamrin School of Climate Change and Sustainability, IESR organized a public discussion webinar entitled “Indonesia Mampu Capai Netral Karbon sebelum 2070”. The webinar aims to be a means of public participation in responding and providing input to the government on public policies concerning the interests of everyone’s life.

In his remarks, Fabby Tumiwa, Executive Director of IESR, said that the recent increase in hydrometeorological disasters could be due to the climate crisis phenomena. This is in line with the IPCC’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report which states that an increase in Earth’s temperature by 1.1 degrees since pre-industrial times has increased the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather.

According to Fabby, the pressure from various parties, especially the government to increase its ambition in responding to the climate crisis is important.

“We want to encourage ambitious efforts that require not only a different way of thinking but also commitment and leadership from our political leaders, the president, who should be able to see that this climate crisis has an impact on the lives of many people,” said Fabby ending his remarks.

Farhan Helmy, Principal of the Thamrin School of Climate Change and Sustainability also agrees that Indonesia’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2070 is far too long. In his remarks, Farhan explained that there are at least four points that are often missed in climate discussions, i.e (1) the absence of coherence in the climate agenda and policies, (2) there is no serious effort to involve non-state actors, including cities that are spearheading the process changes, (3) the scale of action which is still at the pilot project level is not yet an institutional transformation supported by economic transformation, (4) a change of leaders without any fundamental rules on climate makes policy direction less clear.

“Indonesia cannot do this alone. The role of the state can no longer be just procedural to follow negotiations, “said Farhan.

One of the sectors that have come under the spotlight to achieve carbon neutrality is energy. It is important to understand the energy system and increase the ambition to reduce emissions in the energy sector because this sector is the largest emitter. Deon Arinaldo, program manager of the Energy Transformation, IESR, explained that there are several steps that can be taken to decarbonize the energy system.

“A more ambitious energy transition scenario can be achieved if, (1) there is no new coal-fired power plant (PLTU) construction starting from 2025, (2) The initiative of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources to replace 13.5 GW of fossil plants with renewable energy is implemented, and (3) carries out the phase-out Steam Gas Power Plant (PLTGU) and Diesel Power Plant (PLTD),” he said.

Deon also added that technically and economically, Indonesia is able to carry out the steps above and decarbonize the energy system before 2050. What is needed is comprehensive political commitment and support.

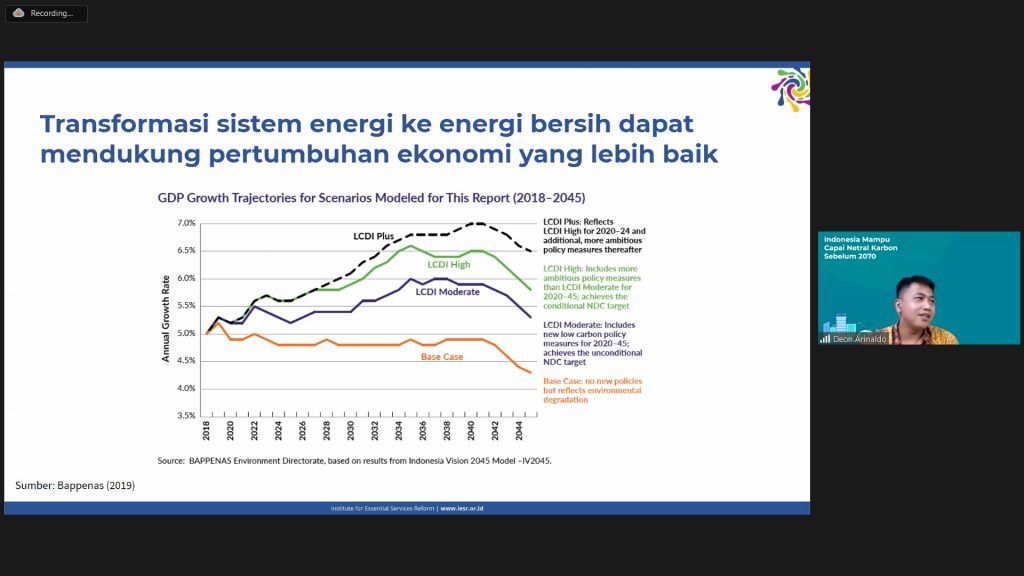

Several years ago, Bappenas released a report on Low Carbon Development Indonesia; which shows that the Indonesian economy is increasing even though we use the Low Carbon Development concept in development. So the doubt and assumption that doing development with a low carbon concept is expensive, and will have an impact on stagnating economic growth have been actually answered by this report clearly.

Anggalia Putri, Knowledge Management Manager of Yayasan Madani Berkelanjutan, added that Indonesia has an interest in achieving the target of 1.5 degrees C rather than 2 degrees to avoid climate risks such as hydrometeorological disasters, for example, increasing floods. In the Indonesian context, many unique ecosystems will be destroyed if we cross the 1.5 degree limit.

“There is a significant difference in climate impacts between 1.5 and 2 degrees, so we stick to it to reach 1.5 degrees,” said Anggalia.

Furthermore, Anggalia added that with the existence of a net sink in the FOLU sector in 2030, Indonesia could actually reduce its deforestation quota.

Ari Mochamad, Country Manager of ICLEI Indonesia, emphasized the role of cities that are also crucial in reducing emissions and the journey towards carbon neutrality. “The city contains both problems and solutions. 70% of greenhouse gas emissions come from urban activities, but on the other hand, the city is a place that can be managed. Several leaders and non-government actors have made the issue of climate change a necessity because its impacts are already before the sight, “he concluded.

Several cities in Indonesia are members of the Global Covenant of Mayors (GCoM), a commitment from city leaders across the country who realize that climate change is a necessity so that it changes the mindset in decision making.

Indonesia’s target to achieve carbon neutrality is an important issue regarding transgenerational justice between our generation and our children and grandchildren generation.

Yuyun Harmono, WALHI’s Climate Justice Campaign Manager emphasized that Indonesia’s target to become carbon neutral by 2070 is way too late.

“It is clear that it is too late if our target to be carbon neutral is in 2070, many country leaders and even the UN Secretary-General have stated that the current condition is a climate emergency, we must be ambitious in setting targets and taking action. We need something (policies) that are fast, both developed and developing countries.”

On the other hand, there are many loopholes to shrug off ambitious emission reduction obligations such as carbon trading offsets schemes to developing countries. This scheme will make developing countries have to bear a double burden in the future, namely the offset burden of developed countries and the emission reduction targets of their respective countries.

Regarding justice across generations, Yuyun emphasized that we should ask what we want to pass on the earth’s condition to our future children and grandchildren.

“Are we going to ensure they are safe from the ecological crisis and the climate crisis? Or are we leaving something that will make them unfortunate in the future? In climate justice, justice between generations is also an important context, so it must be considered. We want to demand more ambitious climate policies that reflect justice between generations and climate justice, “said Yuyun at the end of his presentation.

Closing the webinar, Dian Afriyanie, committee member of the Thamrin School of Climate Change and Sustainability, highlighted two points as the key takeaways of the webinar. First, the importance of coherence between government policies in addressing the root of the problem; and policy coherence across sectors, locations and government hierarchies.

“The results of the IESR and Madani research show that the government’s target for emission reduction in the energy sector and FOLU can still be increased and accelerated, so the government should not only carry out procedural negotiations but also see and refer to the findings of this research,” said Dian.

Second, the deliberative process in policy formulation. P articipation and representation of various groups is indeed a challenge in itself during this pandemic, however, in the formulation of public policies this process must be pursued, so that the policy products really belong to the public.

articipation and representation of various groups is indeed a challenge in itself during this pandemic, however, in the formulation of public policies this process must be pursued, so that the policy products really belong to the public.