Jakarta, February 12, 2026 – In January 2026, the United States (US) announced its intention to withdraw from climate negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This move follows the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in January 2025.

This decision has the potential to affect climate funding allocations for developing countries, including ASEAN member states. Erina Mursanti, Deputy Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR), emphasized that even though the US is withdrawing from the global climate arena, ASEAN must continue its energy transition and position it as an engine for sustainable economic growth.

According to her, multilateral institutions such as ASEAN play an important role not only in promoting climate finance, but also in providing technical assistance, policy guidance, and platforms for regional coordination.

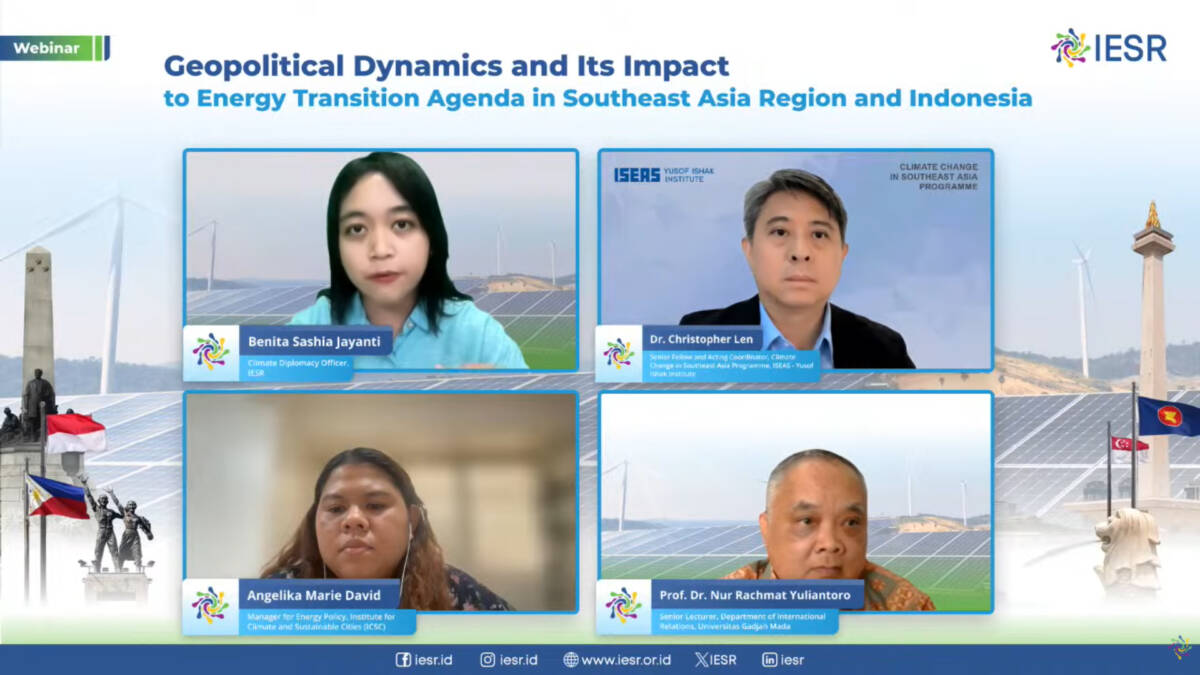

“ASEAN, especially Indonesia’s role in Asian and global forums, can help Indonesia as a country to bridge geopolitical gaps and strengthen South-to-South cooperation to support fair access to climate finance and clean energy technologies,” said Erina in the Webinar on Geopolitical Dynamics and Their Impact on the Energy Transition Agenda in Southeast Asia and Indonesia (12/2).

Undeniably, as a region that still relies heavily on coal, ASEAN requires significant investment to transition to clean energy. Christopher Len, Senior Fellow and Acting Coordinator Climate Change in Southeast Asia Progamme, at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, revealed that based on findings from the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2023, ASEAN needs at least USD 200 billion per year in clean energy investment until 2030. However, the mobilization of new funds has reached only around USD 30 billion per year. He believes that the US withdrawal could undermine Southeast Asian countries’ confidence in the sustainability of US climate commitments.

“Our coal phase-out plans have been disrupted. In March 2025, the US withdrew from the Just Energy Transition Partnership Agreement with Indonesia and Vietnam, and this move terminated direct US climate financing commitments for Southeast Asia’s coal phase down, which affects over $3 billion in pledged support,” explained Christopher.

To remain resilient in the face of geopolitical pressures, Christopher encourages ASEAN to take three strategic steps. First, develop innovative financing mechanisms, such as debt-for-climate swaps and climate-resilient debt clauses, which allow debt payments to be redirected to climate projects. Second, strengthen inter-regional diplomacy, particularly with partners such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Australia, to expand financing support and enhance leadership in clean energy policy. Third, strengthen internal ASEAN coordination so that the region has a more solid bargaining position in global forums.

“The geopolitical landscape for climate cooperation looks very different today than it did two to five years ago. The US retreat from climate leadership, coupled with broader global fragmentation in multilateral institutions and geopolitical competition, creates real challenges for Southeast Asia and the Global South. However, this moment of uncertainty also presents opportunities. ASEAN and the Global South are not passive recipients of the climate agenda set, and I believe that our region, and the Global South as a whole, has the agency to shape our own climate futures,” he said.

Prof. Nur Rachmat Yuliantoro, Senior Lecturer in the International Relations Study Program at Gadjah Mada University, believes that the international system is no longer determined solely by power, but by trust.

According to him, for Indonesia as a middle power, the priorities are maintaining strategic independence, regional stability, and sustainable development amid geopolitical instability.

“Energy transition is not just a shift from fossil fuels to clean energy. It is part of geopolitical strategy and foreign policy,” said Nur Rachmat.

He added that Indonesia is now moving from a traditional non-alignment approach to active strategic non-alignment, which means remaining neutral while actively building broad relationships to gain strategic benefits. This approach requires strong diplomatic capacity, economic resilience, solid institutions, and credible regional leadership.

Angelika Marie David, Energy Policy Manager at the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC), emphasized the importance of civil society involvement in the energy policy process in Southeast Asia. According to her, civil society can help shape diplomatic messages, influence national positions, and sustain dialogue within ASEAN bodies and the Secretariat.

“Sustaining energy transition amidst geopolitical uncertainty requires regional collaboration, robust institutions, and active engagement of non-state actors,” she concluded.