In the latest draft of Indonesia’s national energy policy (KEN) and its roadmap, the introduction of a nuclear power plant (NPP) is scheduled for 2032. Initially, it is planned to contribute 250 MWe, comprising 0.4% of the energy mix, with a projected by this policy to be increased up to 11.4% by 2060 within the Indonesia Energy System. This capacity is primarily proposed through the promotion of TMSR500 (2 x 250 MWe) to the National Energy Council of Indonesia, intended to be operated on Gelasa Island, Central Bangka Belitung. TMSR500 represents an emerging/underdevelopment nuclear reactor design, integrating “new” combinations of moderator, coolant, fuel, and scalability of features, utilizing graphite, molten salt, thorium fuel, and small modular reactor technology.

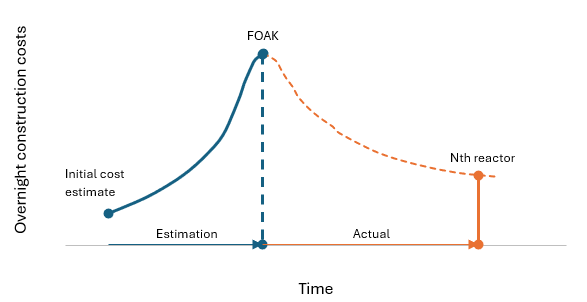

First-of-a-Kind (FOAK) nuclear technology, including the thorium-MSR reactor by its very nature, potentially presents a significant challenge in terms of cost and construction timelines as illustrated in picture below. Recent studies of Gen-III/III+1 projects reveal a concerning trend: the last five FOAK projects have experienced delays in construction, surpassing initial estimates by a staggering 2.3 times. Additionally, these projects have incurred costs that are 2.3 times higher than the originally announced budgets. Even the latest advancements, such as Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) exemplified by Vogtle 3 and 4, have encountered similar challenges as of FOAK Gen III projects. The replication of these issues across different technologies underscores the need for a critical examination of the risks associated with FOAK NPPs.

Source: NEA. 2020

Source: NEA. 2020

In power plant financing and structure, two bases are commonly used: limited-recourse and recourse. Since there are no existing assets for the first nuclear power plant, limited-recourse financing, also known as project financing, was employed. This means the capital raised is solely backed by the project itself, same as most renewable projects. In this instance, a separate corporate entity, acting as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) company, was established to develop and operate the NPP. The entity is primarily funded by business-based revenue and some investors as sponsors.

Similar to many operating Nuclear Power Plants (NPPs), public (government) financing was utilized to secure government involvement and ensure majority ownership in the projects, facilitating easier access to cost-effective debt. Likewise, the NPP Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) company aimed to collaborate with State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) to establish a joint operational entity, further cementing government involvement in the project through SOE. So, in this case, public (government) money through SOEs will be involved in the project.

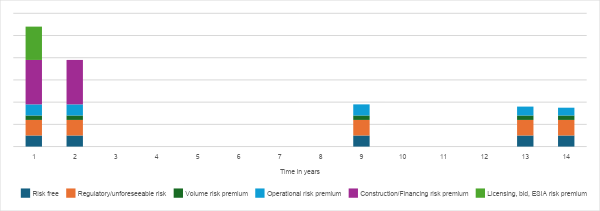

Therefore, as representatives of the Indonesian public, we need to comprehend the risks faced by SOEs, shareholders, and other stakeholders, including EPC suppliers for components/construction. Currently, as the NPP project has not yet reached the licensing and bidding stages by the off taker, the accumulation of risks, such as bid risk premium, construction/financing risk premium, operational risk premium, volume risk premium, regulatory/unforeseeable risk, remains very high, indicating a high risk of default. As the project progresses, it accumulates assets, thereby reducing risks. However, from the start to the COD phases, rules prohibit the sale of these assets to other parties.

Source: IETO IESR. 2024

Source: IETO IESR. 2024

The chart above serves as an illustration of risk reduction progress in each phase. However, regarding FOAK NPPs, we can imagine the considerable risks involved in construction/financing, licensing risk premiums given their FOAK’s poor track record. Consequently, insurance costs (covering construction all-risk, delay in start-up, logistics, any stakeholders’ liabilities, and environmental factors) for the capital expenditure (CapEx) of FOAK NPP projects are likely to be substantial, not to mention initial operational expenditure (OpEx) insurance. Additionally, with interest during construction and the high risk of delays, stakeholders, especially EPC, may need to bear high risks initially and hold a significant equity stake to defer payment until near COD.

Furthermore, with nuclear cost components comprising 72% of investment, 16.6% for O&M, and 11.3% for the fuel cycle, with almost 85% fixed and 15% variable costs, any cost overruns during construction would significantly impact the LCOE of the plant. Thus, if, for instance, SOEs are involved in operating the plant and undesired events occur, they would bear the resulting losses.

Considering the cost composition of NPPs, despite the IAEA mentioning their potential use as load followers/integration with VREs, NPPs lack sufficiently flexible cost components, with only 15% being variable costs. Moreover, given the high risks and development costs of NPPs, it’s likely that offtakers would adopt repayment schemes like capacity credit or take-or-pay, which offer little benefit and may add incentive costs if operated flexibly. Hence, this is why NPPs are unsuitable for integration with VREs that are increasingly dominant in the market due to their decreasing costs over time.